Future:

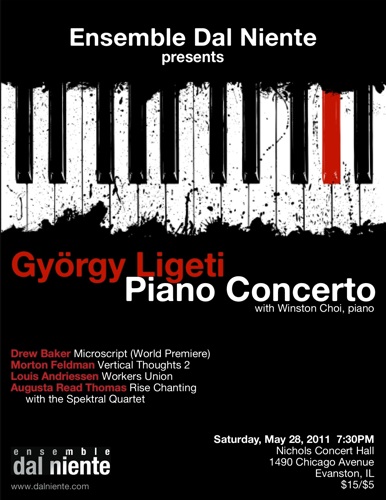

This Saturday, May 28th, Ensemble Dal Niente will premiere my latest work, Microscript for flute, oboe, soprano saxophone, violin, viola and cello. The concert will take place at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston, IL at 7:30pm. I am excited to once again work with Dal Niente, a group that combines uncompromising virtuosity with bold, provocative programming as evidenced by Saturday's concert which will include György Ligeti's Piano Concerto (with soloist Winston Choi), Morton Feldman's Vertical Thoughts 2, Louis Andriessen's Workers Union and Augusta Read Thomas's Rise Chanting (to be performed by The Spektral Quartet).

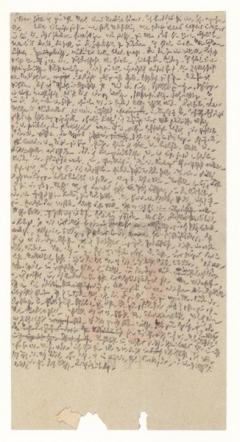

The title Microscript alludes to a series of texts or "microscripts" by the Swiss writer Robert Walser (1878 - 1956). On small pieces and scraps of paper, Walser composed entire stories, poems and, in one notable case, a novel (taking up only 24 pages!) using microscopic handwriting. For years following Walser's death, these texts were thought to be written in some sort of indecipherable code. However, scholars later discovered that the tiny markings (each letter between 1 and 2 millimeters high) are actually a very old form of German shorthand called Kurrent script. This shorthand dates back to Medieval times and remained in use up until the middle of the 20th century.

Walser's "microscripts" are not only fascinating in terms of the literal meanings conveyed, but are also quite striking from a purely visual standpoint. The Painters' Table Blog nicely articulates and elaborates upon this point:

"It’s easy to see why Robert Walser’s “Microscripts” are some of the most visually interesting pieces of 20th century writing. The tightly-packed miniature ‘Kurrent’ script used by Walser presages later developments in drawing – Brice Marden’s shell drawings immediately come to mind as do works by James Castle, Joesph Beuys, Cy Twombly and Henri Michaux.

More interesting than the microscripts’ visual connection with later developments in drawing, however, is the effect Walser’s method has on the resulting prose – namely an uncanny ability to evoke spatial and temporal movement akin to that in painting.

Like paintings, which can be experienced at once as a whole, Walser’s compressed prose (rarely more than a page or two) constructs full narratives than can be consumed rapidly – nearly ‘at a glance’ as it were. Their short length allows the reader to revisit the work in detail, focusing on sentences, phrases, or words as one might examine the painted passages or marks on a canvas."

It is this invitation to examine each work in a highly focused manner that ultimately interests me. The piece I wrote for Dal Niente is not intended to provide any sort of literal connectivity to Walser's stories or his idiosyncratic script. I am not attempting to musically depict one of his plot lines, set his text or develop some sort of musical shorthand in order to fit an entire piece onto a scrap or two of paper.

Rather, I want to create a similar sense of focus and intensity. I want the listener to gain a heightened awareness of the sonic detailing and I seek to do this in part by limiting certain parameters in order to emphasize others. Microscript begins with nearly two minutes of a single pitch. This seemingly static handling of pitch serves to elevate one's sense of articulation, which in this case - with constant changes in string assignments, bow contact points, articulations, etc. - is quite diverse. It is my hope that the physicality of the sound is as apparent as that of Walser's writing and I furthermore wish to grant the listener the freedom to linger over and carefully examine various gestures and textures.

Again, I'm very much looking forward to working with Dal Niente and I hope to see you at the performance.

Past:

Below are recordings from two recent performances of my works. On April 23rd, Jonathan Katz performed Stress Position for solo amplified piano at Northwestern University's Lutkin Hall. On April 24th, The Talea Ensemble performed Inter for flute, bass clarinet, violin and cello at The Roger Smith Hotel in NYC. I want to thank Jonathan and Talea for their generous support and their beautiful playing.