The piece takes its name from a drawing by Antonin Artaud created during his last days in the asylum at Rodez...I describe it as a monodrama because it is scored for only one singer...there is no text, no plot, and no stage directions predetermined whatsoever...the drama is contained in the music and the title...the visual interpretation of it is left up to the imagination and creativity of the director, stage designer, and singer to decide...it is my hope that the stage presentation somehow draws inspiration from the spirit of Artaud, his art, philosophy, and writings...but from there on the possibilities are wide open...

-John Zorn on his monodrama, La machine de l'être

Watching John Zorn's La machine de l'être and Morton Feldman's Neither at The New York City Opera left me wondering how one goes about staging works that are so highly abstract? Both "monodramas" seem inclined toward a dramatic setting, especially given that each incorporates an extremely virtuosic solo soprano part. But the complete lack of text in the Zorn and the elusive quality of Beckett's words in the Feldman, offer little in the way of direction. Who do you put on stage? What will the performers do?

In the case of La machine de l'être, the following occurs:

Two manequin-like figures, male and female, both dressed in dark suits, stand silently at the lip of the stage as the audience takes their seats. The house lights dim and the curtain rises revealing a large group of people wearing black burkas standing perfectly still against a dark background. The suit-clad figures who had previously stood at the front of the stage now quizzically walk around and eventually remove the burkas from two people, exposing a man in a bright red suit and a woman (the solo soprano) in a black dress. All of this occurs before a single note is played.

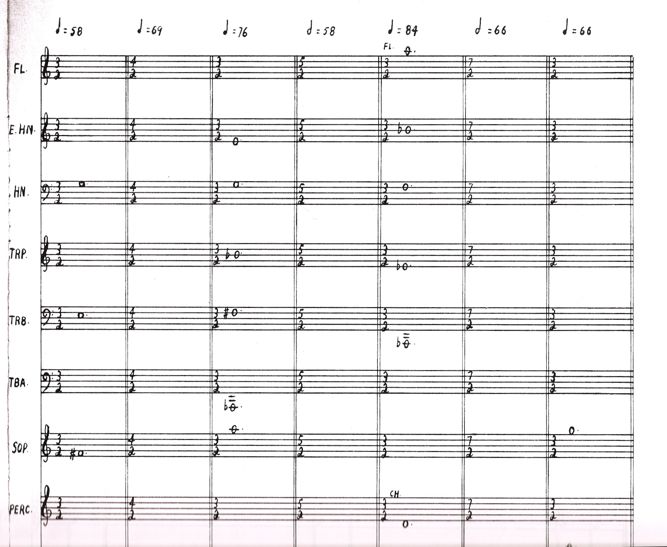

When the music finally begins, two large screens, both in the shape of cartoon thought bubbles, emerge from beneath the stage and hover above the burka people. Adaptations of Artaud's drawings are projected onto the screens. Another person is deburka-ed, this time it is a woman wearing what appears to be a very short, white night gown. Odd choreography ensues including burka people executing movements that bizarrely resemble voguing. Eventually the man in the red suit, along with one of the thought bubbles, disappears into the rafters. The other thought bubble bursts into flame. Fin.

Some of the visual elements (the thought bubble screens in particular) are clearly taken from the Artaud drawing of the same name. That said, much of the staging, regardless of relevance to Artaud, comes off as campy in a way that distracts from Zorn's score. It seems odd to incorporate such overtly political imagery into a wordless piece. One is automatically compelled to search for specific meanings and context. And yet, at the risk of cattiness, I must nonetheless confess that the the depth of inquiry here could be summed up in the following manner: Q. What's under the burka? A. People.

Zorn's statement that "the drama is contained in the music and the title" would seem to call for a staging that, at the very least, finds a way to both complement and elevate the overall sonic intensity. The notion of severely limiting the interaction between composer and choreographer/director is not new (i.e. Cage/Cunningham). Regardless, it is a very dangerous scenario that can easily go awry as evidenced here.

Thankfully the production of Feldman's Neither was devoid of political imagery. Before discussing the staging, I must say that this is some of the most stunning music I've ever heard. An entire orchestration class could be taught using nothing but this score. Unlike the Zorn, where I found myself distracted by the staging, Feldman's music continuously drew me in and had me staring into the orchestra pit throughout. With the noted exception of soprano Cyndia Sieden's mesmerizing performance (worth the price of admission alone), the visual happenings on stage almost seemed unnecessary.

That said, the set for the Feldman was certainly striking. The stage walls reminded me of the silver, reflective material used on fire-retardant suits. Mirrored boxes on wires were raised and lowered at various points throughout. The overall vibe leaned toward the surreal, as though entering the champagne room of a nightclub with lights swirling around a cluster of catatonic-looking people. James Holt on Twitter (@myearsareopen) appropriately likened it to a David Lynch film.

All in all I found the lighting to be the most effective staging element. One moment that truly stood out featured a flickering strobe beautifully integrated with syncopated wood block strikes bouncing back and forth around the orchestra. More problematic was the choreography. In addition to the solo soprano, a group of dancers moved about the stage (at times a bit noisily) throughout. Similar to the Zorn there were hand gestures that that seemed straight out of 80s pop culture, perhaps not voguing, but far too close. Other moments were more reminiscent of Robert Wilson's Einstein on the Beach choreography. I was particularly bothered by the way in which one by one the dancers exited the stage as the piece came to a close. Feldman's music is essentially without beginning or end. It is more akin to a cloud formation that floats into your consciousness and slowly moves on to parts unknown. To choreographically signal the end seems wrong.

Criticisms aside, it is indeed difficult to maintain visual engagement for 50 minutes. Part of the genius of Feldman is his ability to create textures that may seem static or repetitive, but upon closer listening are constantly shifting. This puts a clear onus on the director to find a visual correlation, a setting that is equally subtle and varied. I don't know that the New York City Opera's production succeeded from this standpoint, but unlike the Zorn, the avoidance of extramusical, political themes kept the focus where it should be, on Feldman's music. Perhaps the best staging would be total darkness.

Note: The New York City Opera's Monodramas production also features Schoeberg's Erwartung. I chose to focus on the Zorn and Feldman given that the former is receiving its world stage premiere while the Feldman is being staged in the U.S. for the first time.