As yet another school year has come to a close, I am left wondering the following: Should beginning composers be allowed anywhere near notation software?

Composers who have devoted years to learning Finale or Sibelius know that the default settings on these programs often generate scores that contradict many long-held notational standards. Composers should be expected to, at the very least, identify and correct such inaccuracies. True mastery might be understood as the ability to achieve, via Finale or Sibelius, the unlimited creativity inherent in a blank piece of paper. This means being able to personalize the appearance and functionality of your score, whether implementing graphic and other "unusual" forms of notation or simply customizing certain cosmetic elements such as where the meter is placed, cross-stemming pitches between staves, etc.

But all of these skills - from identifying the software's anomalies to implementing a truly unique visual appearance - depend upon a deep understanding of notation outside of the software context. This was less of a problem in the 80's and 90's, when composers who began using Finale did so after spending at least some time notating by hand. I will never forget my first attempts at hand-written notation. I was baffled by the extent to which it felt foreign to manually generate the very symbols I had been reading for years. This process of "graphic re-orientation" not only helped me learn to notate, it made me pay greater attention to the notation of others. If I didn't remember exactly how to draw a symbol or indicate a certain sound, I looked at printed scores.

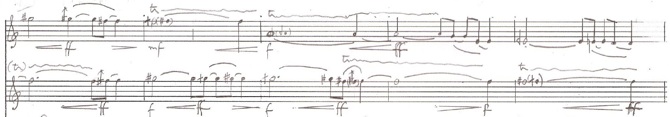

Today's students are engaging in the musical equivalent of learning to type before learning to write by hand, and doing so without spell or grammar check. When you combine a lack of notational experience with a still-developing theory background, you get dotted quarter notes that begin on the second half of beats, nonsensical beamings, and wildly incorrect spellings of chords - none of which the software corrects.

Sadly, this is not be the worst part of the situation. MIDI playback is solely responsible for several evils. It undermines the development of the inner ear. (To quote Aaron Copland: "You cannot produce a beautiful sonority or combination of sonorities without first hearing the imagined sound in the inner ear."*) It causes students to falsely equate the play button with the abilities and tendencies of living, breathing musicians and their instruments. This is especially true with tempo markings, but, as one of my colleagues pointed out, MIDI playback also fails to point out balance issues that arise when certain instruments are put into weaker registers. The playback feature further deludes students into prizing fast-paced textures over those that are less rhythmic and often more sonically nuanced. In the end, certain software features may help us hear things in new and exciting ways. MIDI playback is not one of them.

So what is the solution from a pedagogical standpoint? To me it begins with ensuring that young composers have some experience with hand-written notation. I recently asked students in my Composition I class to write a brief paper reflecting on their final compositions. Here is what one student wrote (reprinted with the student's permission):

"One thing I did find important was writing out my own score...I became much more familiar and close to my own piece. Every note, rest, and bar line was processed through my hand and this gave me comfort in knowing that I had complete and ultimate control over what was to go on my staff paper."

The key words in this statement are familiarity, comfort and control. One of the primary purposes of writing down music is to facilitate the hashing out of sonic ideas - to, as my student puts it, become familiar with the core ideas driving one's own musical discourse. Writing down music is not merely a means of communicating detailed information to performers - the page itself is an arena for exploration. How will the sounds be ordered? What is the best manner in which to visually present the material? A blank sheet of manuscript paper (or better yet a blank piece of paper) allow for direct, unencumbered engagement with these very important questions.

In addition to at least temporarily delaying the use notation software, more emphasis must be placed on score reading. One idea I am mulling over is having students carefully examine one or two scores a week and answer questions that specifically address notational concerns. I know of teachers who make students copy out score excerpts and this may be a useful exercise as well.

I would like to clearly state that I am not completely opposed to notation software. From a larger perspective, I think computer literacy is absolutely essential for all students. The "jolly luddite" syndrome (those who pridefully confess to not knowing how to use certain programs or, even more commonly, social media) that I've witnessed in schools and workplaces alike is appalling . But we must understand notation software for what it is - a troublesome copyist, a musical Bartleby constantly saying to the composer "I would prefer not to." When viewed in this way, we understand that it does not provide a grounding in proper notational practices nor does it facilitate creativity. Therefore, its educational value is severely compromised. I find myself encouraging students to learn how to use notation software so that they are knowledgeable about a commonly used tool, one that they may be required to utilize in a professional context. I wish, however, that my encouragement were bolstered with more substantial, pedagogically-based reasons.

In the end, even professional composers would be wise to hold off on using Finale or Sibelius until after a given piece is completed. When ears and eyes remain free throughout the creative process, one is far less likely to allow notation software to impose upon the final sounding result. Your ears + pencil + paper remain the most vital compositional tools. One may expand upon this dictum to include non-notation software that facilitates acoustic analysis and sound processing. But when it comes to notation, pencil and paper remain a vital part of the overall process. I'll leave you with a recent Facebook comment by Marti Epstein, my very first composition teacher and a composer who continues to generate striking hand-drawn scores:

"When you ask me how I would notate a large orchestra piece, ask yourselves how Mahler notated his symphonies, or Stravinsky his ballets. I fear the grid that the computer can lock us into, I fear that it can make us fast, yet unimaginative. Ask yourselves if George Crumb's music would work better if notated on the computer. I'm not saying everyone needs to copy by hand, but it is worrisome to me that it has become such a lost art that people can't even imagine doing it. Try it once, and see what happens!"

Indeed, the slowness Marti refers to may be perceived as the most threatening part of scoring by hand - a direct contradiction to the speed so valued in myriad contemporary contexts. But slowness and calculation is what enables composers to carefully construct the elaborate textures that make art music of the past and present so fascinating. If Mahler didn't need MIDI playback, you don't need MIDI playback.

* Chapter 2 "The Sonorous Image" from Music and Imagination by Aaron Copland

Postscript: David Smooke recently wrote an interesting post on New Music Box about how his approach to notation has evolved in accordance with his aesthetic evolution as well as an ongoing desire to provide performers with a sense of clarity. Here is a quote relevant to my discussion above:

"Over the past few years, I’ve been changing my approach to musical notation. I began my compositional studies writing conventional scores by hand, but quickly moved into computer engraving. Even as I started to conceive of different ways that I might be able to convey my musical ideas more concisely, I allowed the limitations of the notation software (and in 1994, notation software was significantly more limited than it is today) to direct me down certain notational paths. As I have become more certain about my musical ideas, I’ve begun pushing against the constraints of the software, goading it along a path towards creating scores that convey these ideas as clearly as possible."